OASE 45–46, Christoph Grafe, Barren truth - Physical experience and essence in the work of Rudolf Schwarz

[LINK https://www.oasejournal.nl/en/Issues/4546/BarrenTruth#002]

Barren truth

Physical experience and essence in the work of Rudolf Schwarz

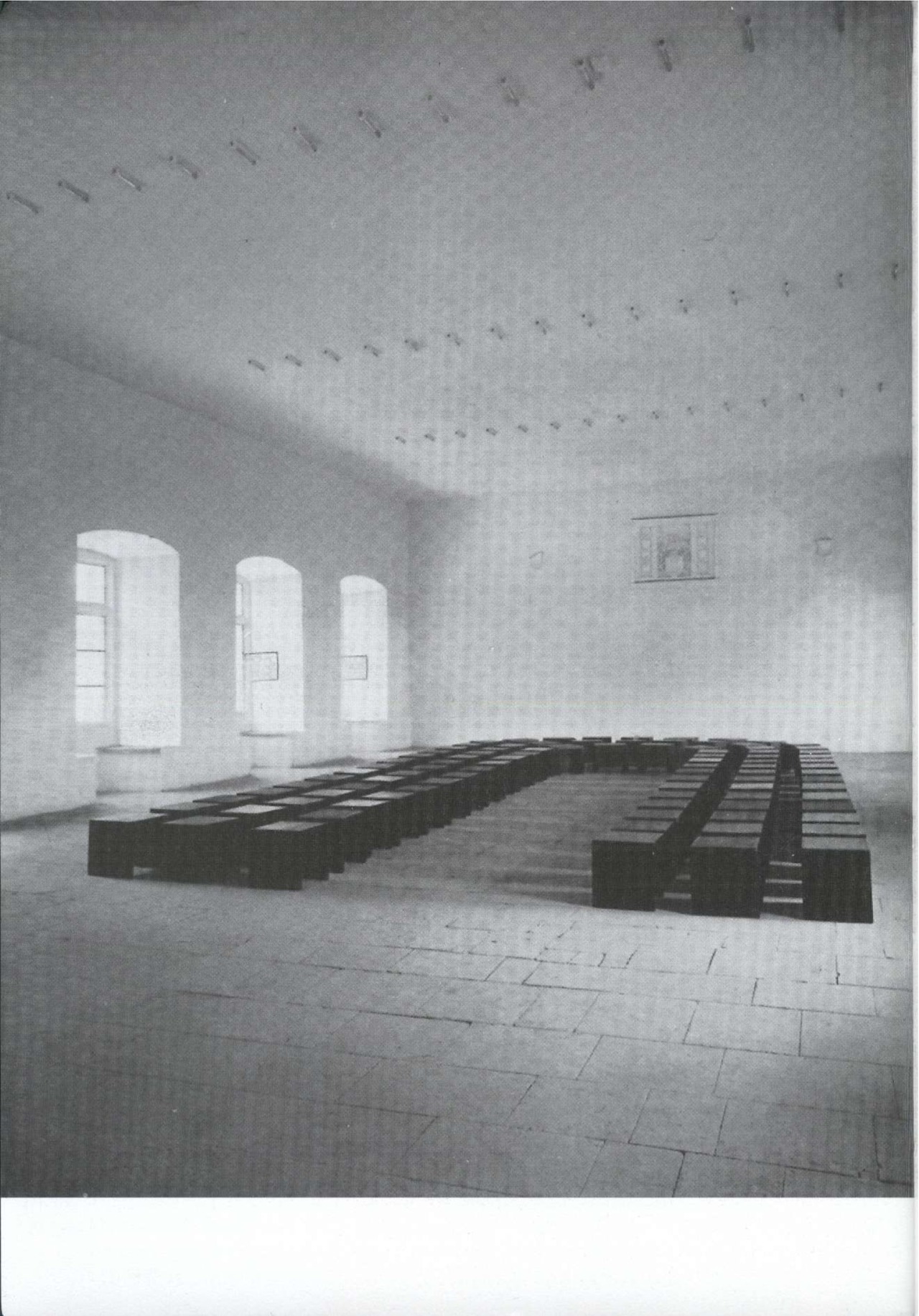

The first photograph of a work by Rudolf Schwarz I ever saw was included in a book with the ominous title Kirchenbau (church building). As I was leafing through this book on a Sunday afternoon, I was immediately struck by a both fascinating and surprising picture: a completely bare white hall, apparently in an old building, with rough stone floors and large windows in deep reveals. In this room there are three rows of black, matte, wooden cubes arranged in a horseshoe, in a way I associated at once with a sculpture which might be found in a museum for contemporary art. The clear lines formed by the stools are echoed by three series of fluorescent tubes fixed to the ceiling. The whole possessed a singular serenity and conveyed a formal precision devoid of any superfluous gesture. The white hall was not an exhibition room but a kind of chapel; a room for the meetings of a catholic reform movement. It was designed by Rudolf Schwarz in the nineteen-twenties. In most books on the history of architecture the name of Rudolf Schwarz (1897-1961) will only appear in a footnote. He is often mentioned in the context of the oeuvre of Mies van der Rohe, who repeatedly put forward Schwarz as one of the people who had been instrumental in forming his architectural thinking.

Schwarz was never a member of any of the 'official' groups of the prewar moderns, despite the fact that his work shows clear similarities to that of his radical contemporaries. Neither was he ever attached to any of the institutions of the 'avantgarde', and this probably accounts for his relative obscurity outside Germany; an obscurity which contrasts sharply with Schwarz' enormous productivity, which resulted in an awe-inspiring oeuvre both as an architect and as a writer. Schwarz perhaps also owes his unique position to the fact that during his career he primarily presented himself as an architect designing buildings for an institution which was met with no more than mild boredom by many fellow architects and architectural critics. From 1926 until the time of his death Schwarz designed some seventy Catholic churches. The majority of these were created towards the end of his life, in the years of conservative reconstruction under the Catholic chancellor, Konrad Adenauer. His most remarkable designs, however, such as the chapel for the Catholic reform movement, Schwarz made at the beginning of his career, while his postwar work is heterogenous in its architectural expression.

Schwarz gained a reputation not only as a designer but also as a critical commentator of the architecture of the Bauhaus period and post-war reconstruction. He was a modern architect who, partly inspired by his Catholic background, and partly by a more broadly motivated critical attitude towards the levelling and alienating tendencies in industrial mass society, reached conclusions which, at the close of the twentieth century, are highly topical. These owe their topicality to their passion to describe as accurately as possible the relationship between physical form in architecture, architectural meaning and perception of space, invariably in search of an architecture which - stripped to its essence - is indisputably present.

Rudolf Schwarz was born in Strasbourg which before World War I was part of the German Empire. During the war Schwarz went to Berlin to study architecture. After completing his studies Schwarz found himself unemployed. He retreated to Burg Rothenfels on the Main for six months. The early medieval castle was owned by Quickborn, a Catholic youth movement. The leading force in this movement was the theologian and philosopher Romano Guardini whose writings also exerted a great influence on Mies van der Rohe.(1) Around the Schildgenossen, the Quickborn journal, a close community was being formed in the twenties which was reminiscent of an academy. Here, theologians, writers and artists met regularly to exchange ideas about social and religious reforms. Since his first stay at Rothenfels Schwarz remained one of the editors of the journal to which he also contributed articles. As an architect, he held a special position in this circle of Catholic intellectuals from the beginning. Guardini himself was very interested in the possibilities of technological progress, and regarded Schwarz as an important discussion partner who, although discerning the problems of modern technology and the trend of alienation in industrial society, was not set against them in advance. The relationship with Guardini and the discussions at Rothenfels left an indelible mark on Schwarz. Later descriptions of this period in Kirchenbau bear out the impression that the intense experience in the old building on the river Main were an initiation for Schwarz' architectural and social thinking.

A t Rothenfels Schwarz worked on his first designs that were to be realised. The first project he mentions himself is not a building, but a gold chalice. Schwarz felt that its simple and lucid form made the significance of the object visible and tangible to the gathered congregation. 'In a sense this cup was my first church', Schwarz wrote in retrospect. Some years later, in 1928, Schwarz actually made the designs for the chapel described above and the communal rooms of the castle. He had the baroque additions which impaired the purity of the room removed, to reveal the volumetric proportions of the room and the rhythm of the windows. The walls and the ceiling are whitewashed, in order to heighten this effect. The dark wooden stools can be placed freely in the room. Schwarz made some rough drafts of interior design alternatives in order to show how the congregation could use the room as it wished. In his description of the design he refers to the chosen poverty which dominated daily life at Rothenfels. By its displayed asceticism, the design of the rooms in which the community gathered for lectures, festivals and ceremonies reflected this mode of life. At the same time, this project shows the direction which the architectural thinking of the now 32-year-old architect had taken since his student days.

Fronleichnamskirche (Corpus Christi)

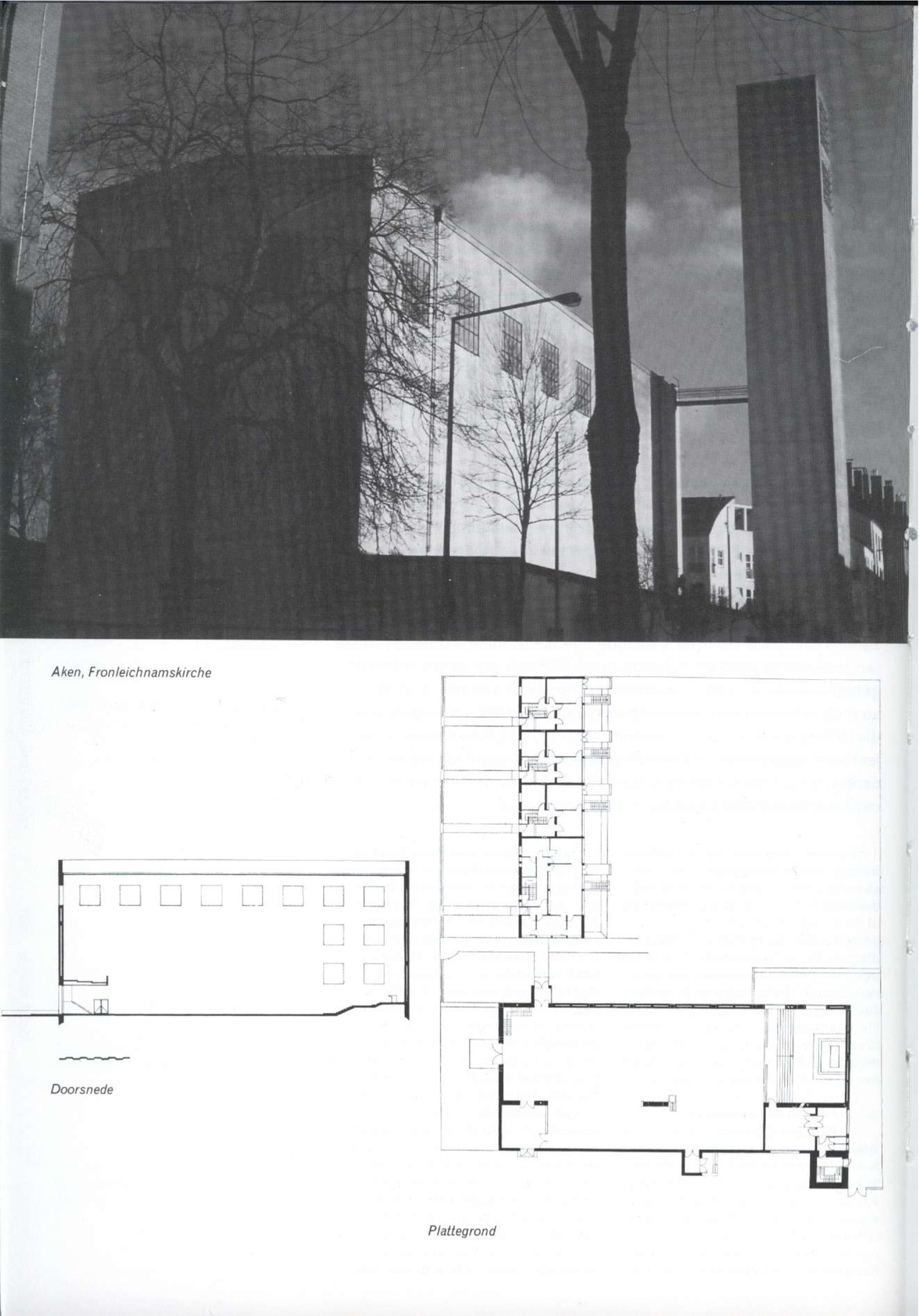

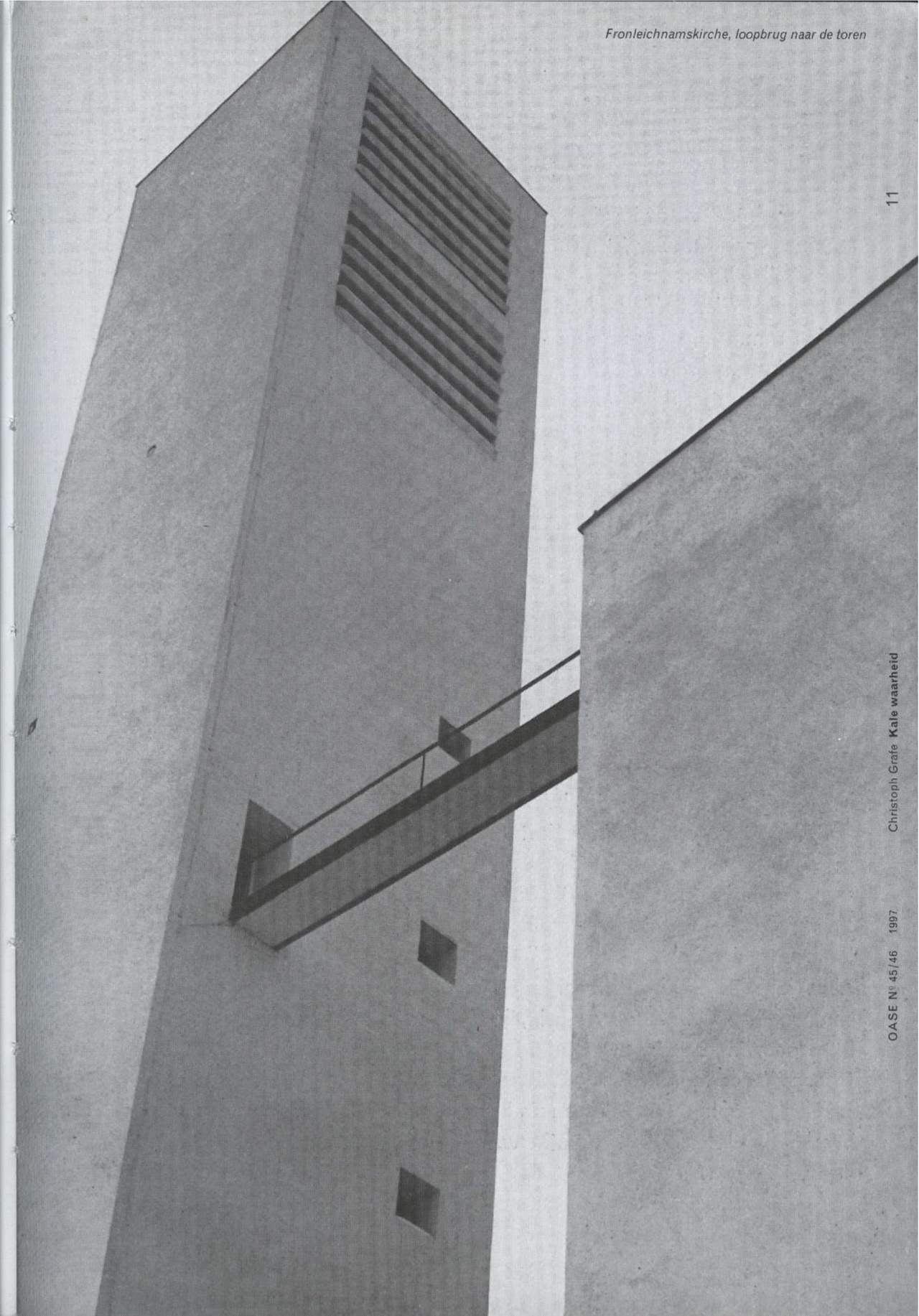

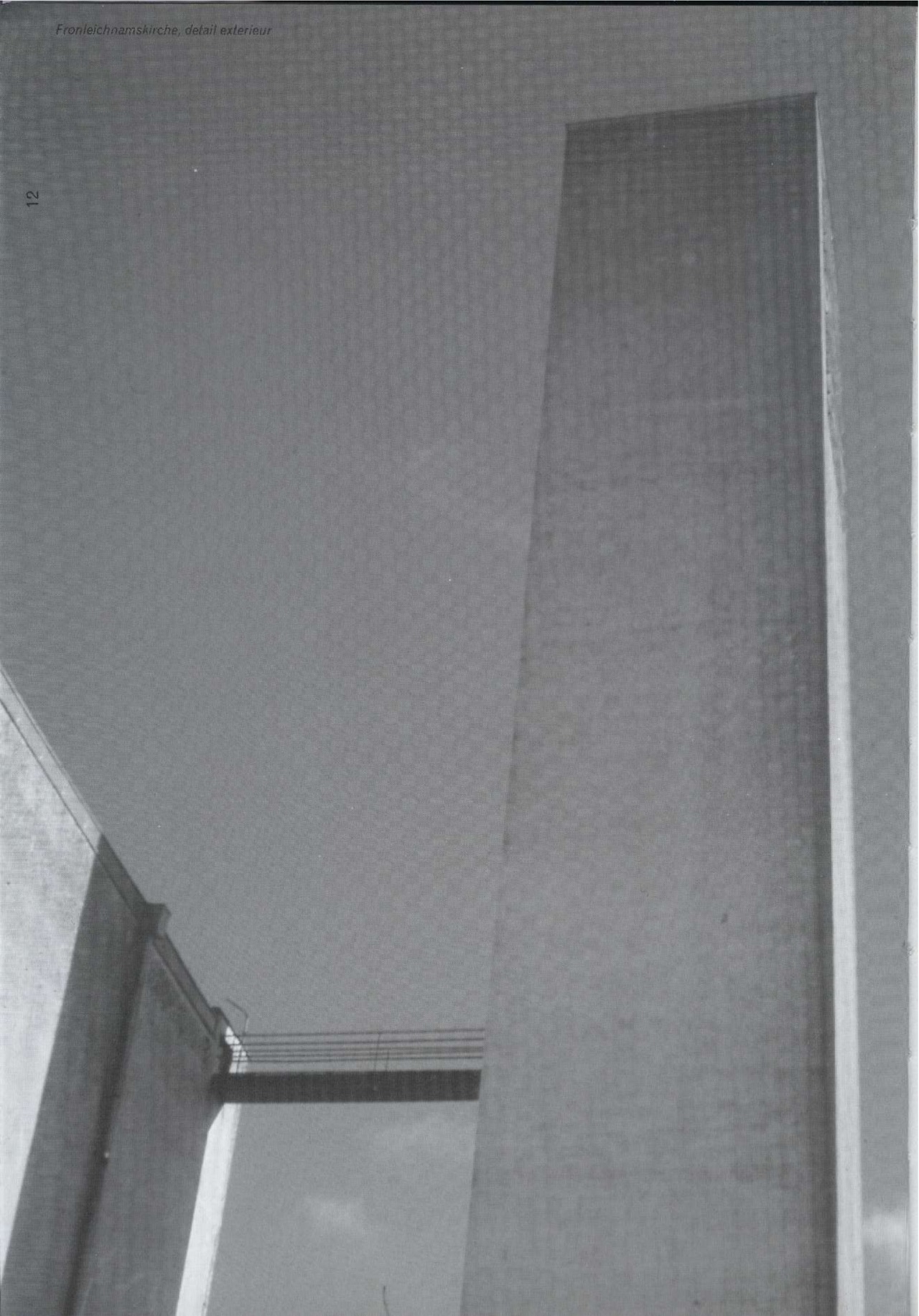

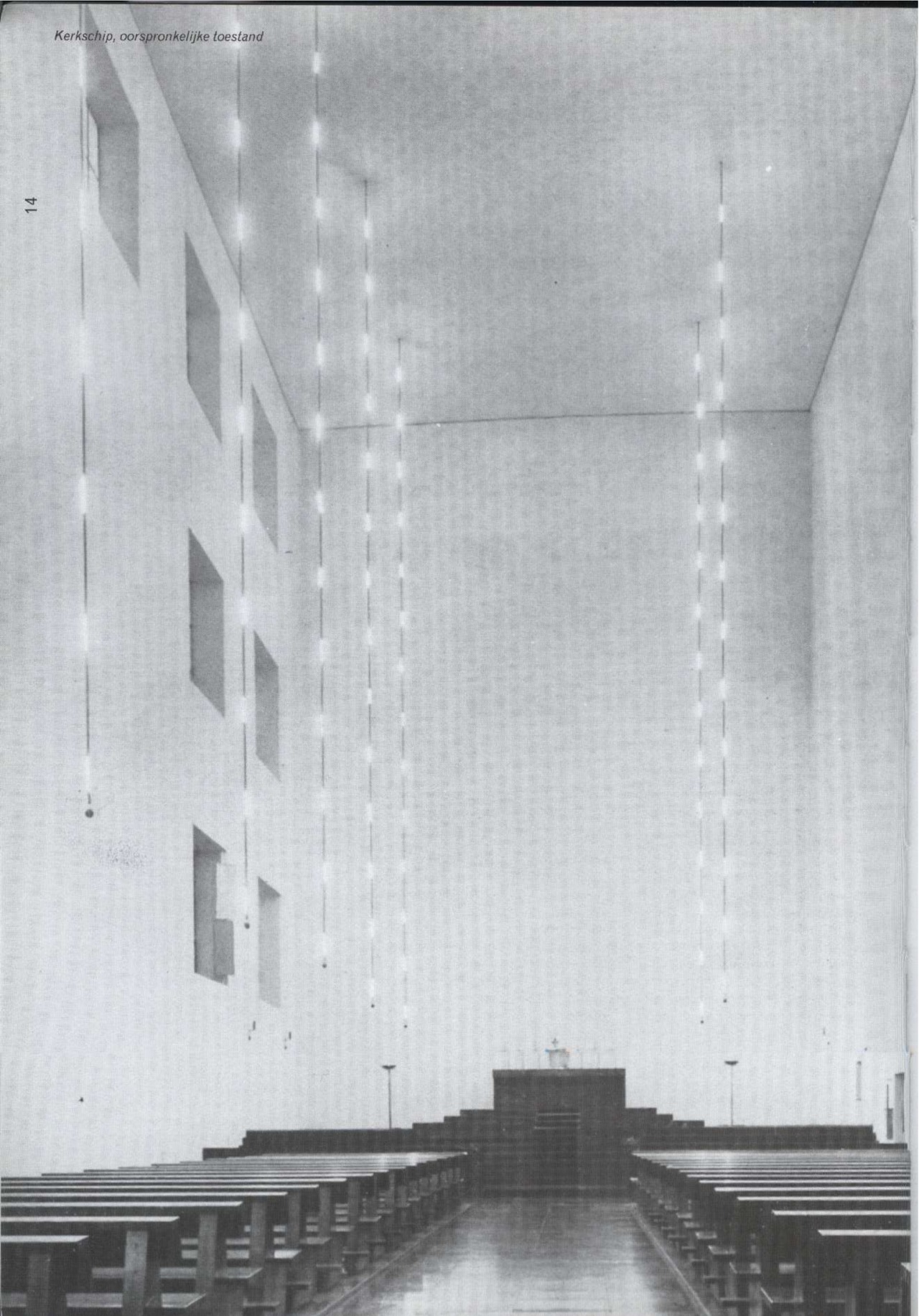

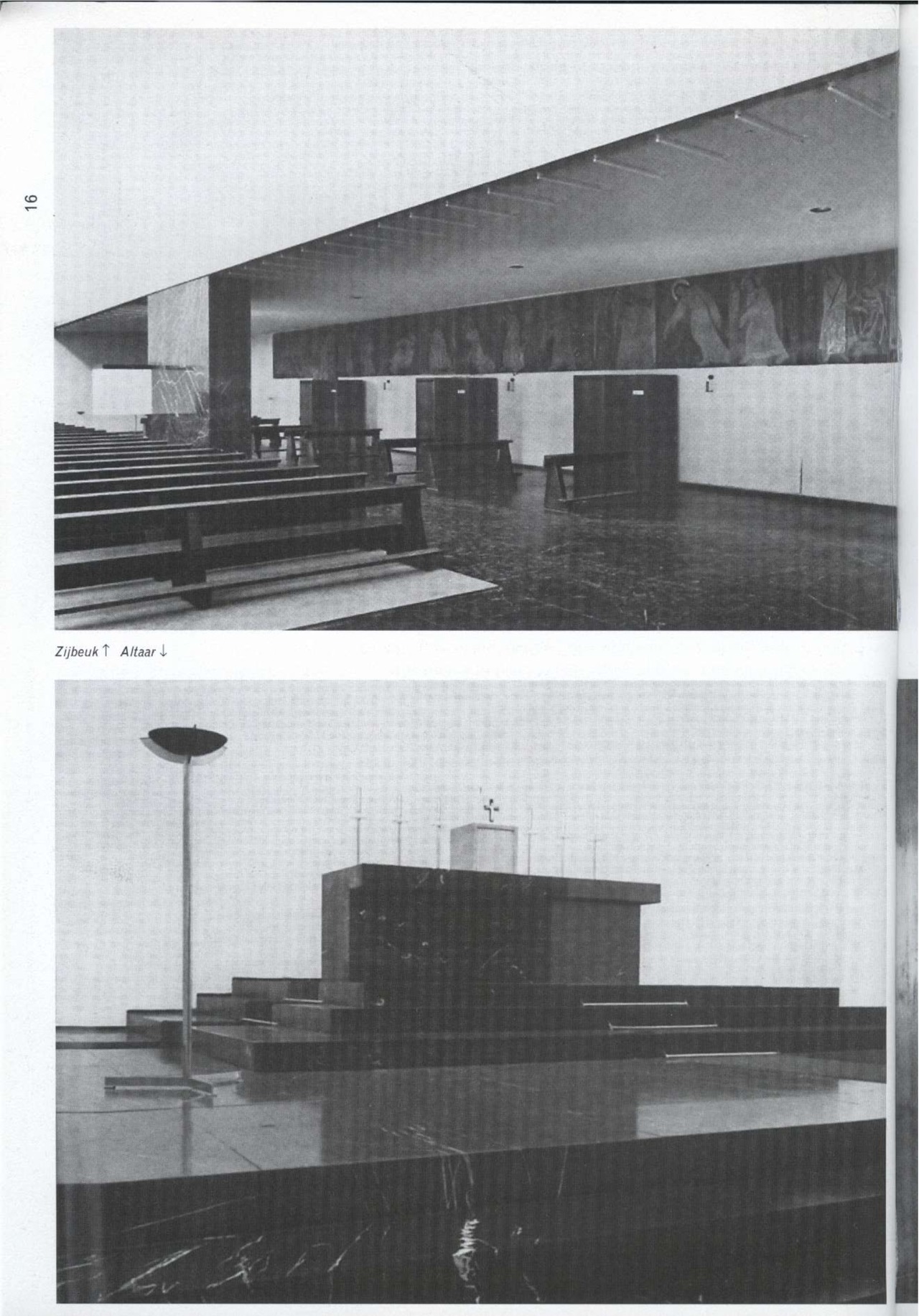

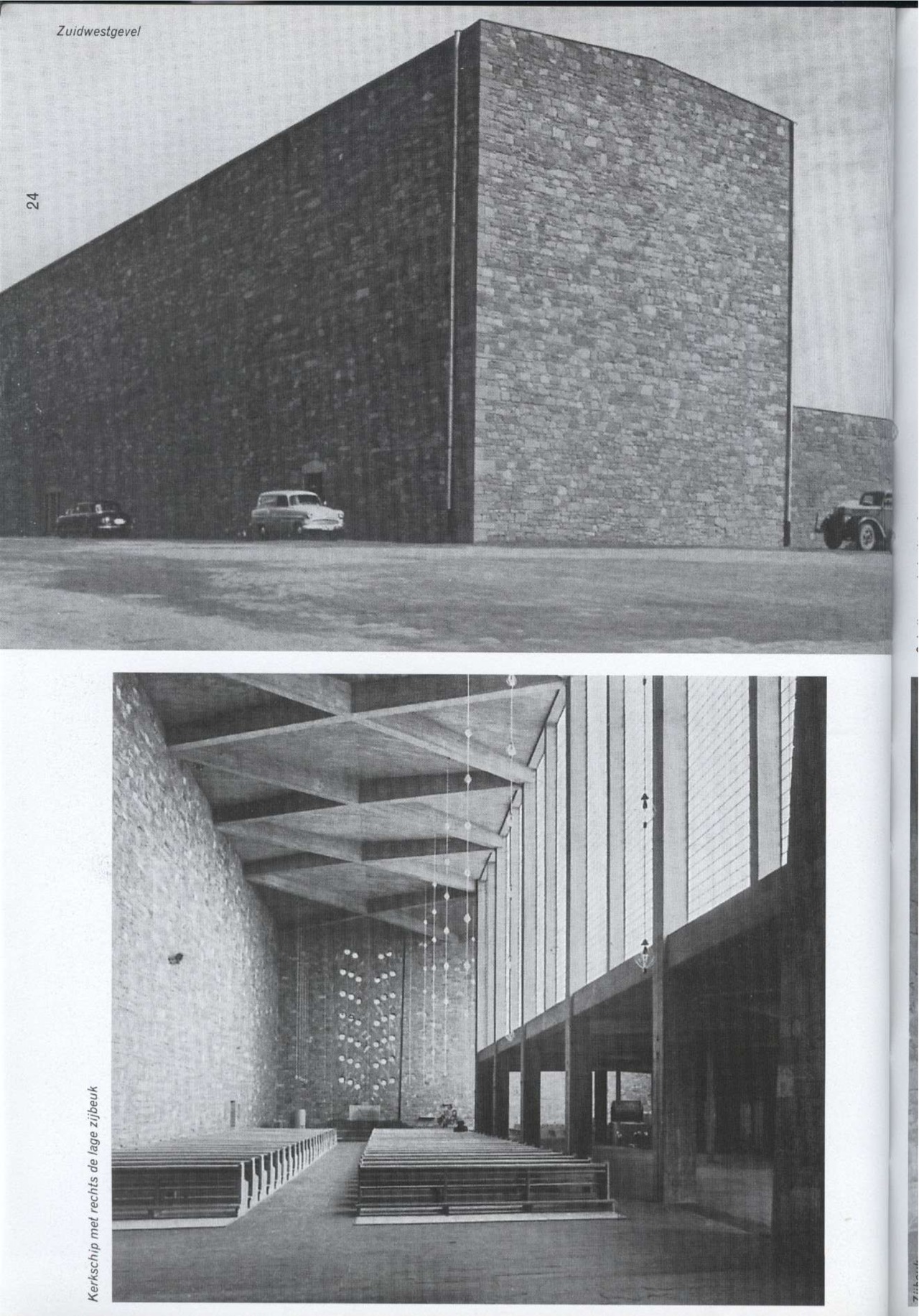

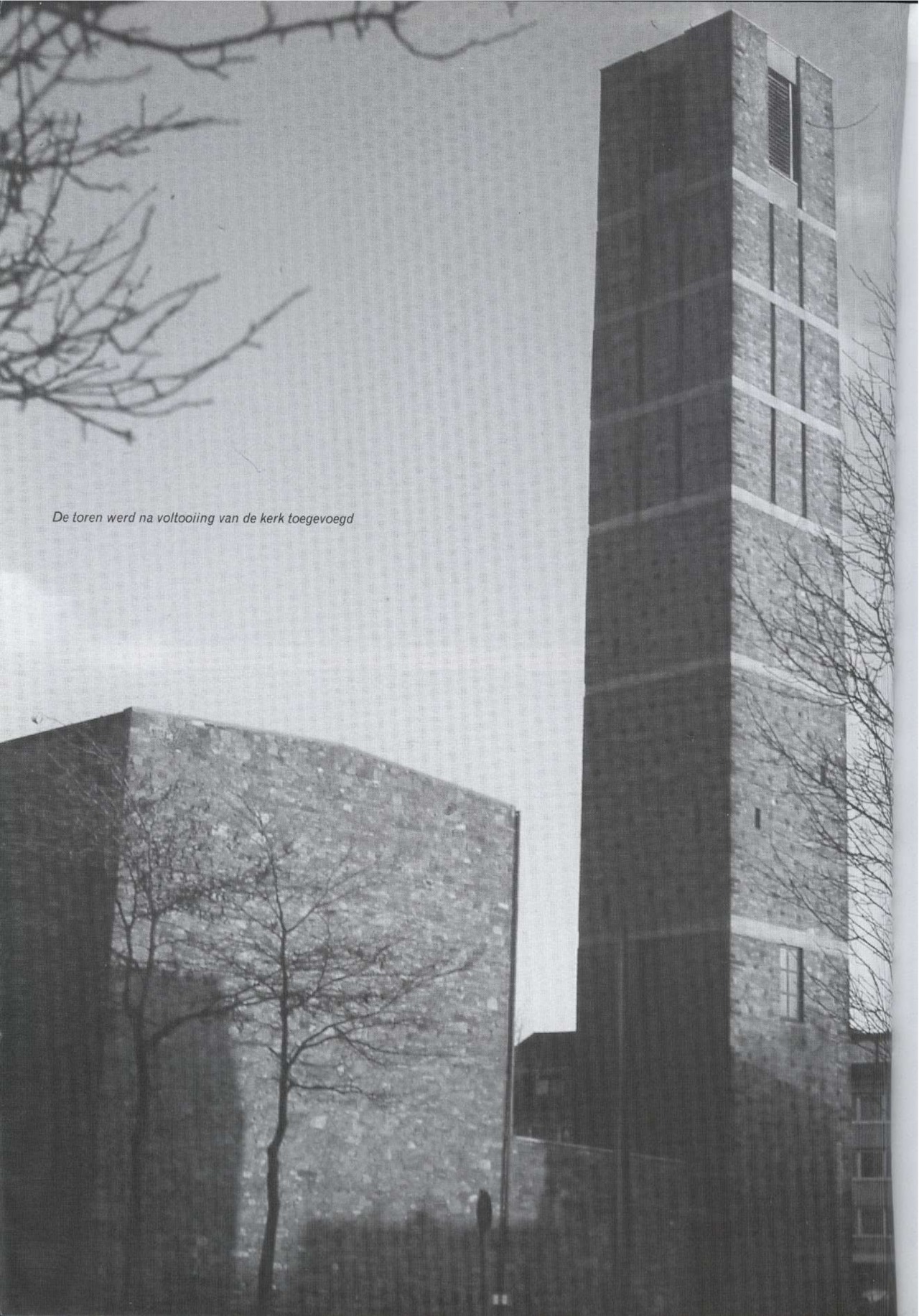

After spending a short period at a technical school near Frankfurt, Rudolf Schwarz was appointed director of the Aachen Kunstgewerbeschule (College for Applied Art). Here he tried to realise the integration of the theoretical and practical aspects of construction which had been lacking in his own education. In his view, the college was a regional Werkhütte, an institution with a responsibility towards the inhabitants of the town and its surroundings. The students were therefore to be given a chance to work at concrete projects for Aachen. The field of activity of this laboratory was to comprise the total scope from interiors to regional planning. In practice, however, the emphasis was - according to Schwarz' own words unintentionally - on designing sacral rooms and objects. At Aachen Schwarz also realised his best-known building in the years following 1928. The St. Fronleichnamskirche was a new church for the order of the Oratorians, a fellowship of priests who ran a parish, but, at the same time, pursued a monastic way of life. The oratories themselves were meant as spiritual centres, functioning both as parish churches and offering the possibility of contemplative prayer. The church is situated at the edge of a nineteenth-century working-class district of Aachen. The high white volume of the nave and the freestanding tower show a strong presence. The church, the tower and the presbytery situated at one side are all finished in smooth white stucco, which both enhances the volumes and which make the church contrast sharply with the grey tenement blocks in its surroundings. This impact is further reinforced by the fact that the wall surfaces are virtually closed. A series of square windows in the upper part of the facades of the nave is the main feature of these. As the windows are set on the outer face of the wall, the walls are not broken and the volume unimpaired.

The church has two entrances, a ceremonial door on the main axis and a lower, double door into the single low aisle on the south side which links the nave with the campanile. Both doors are made of steel and, originally, had a copper paneling.

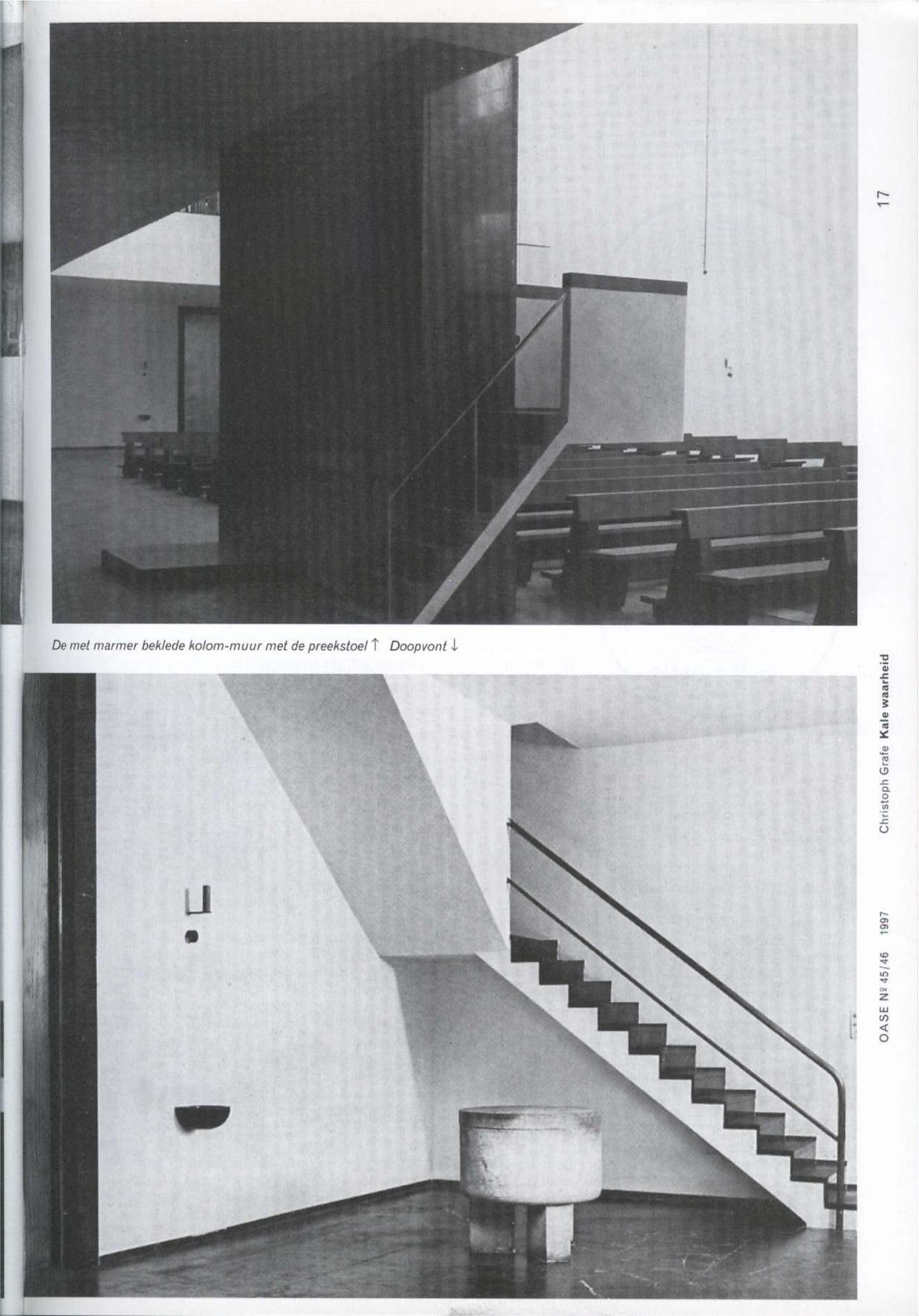

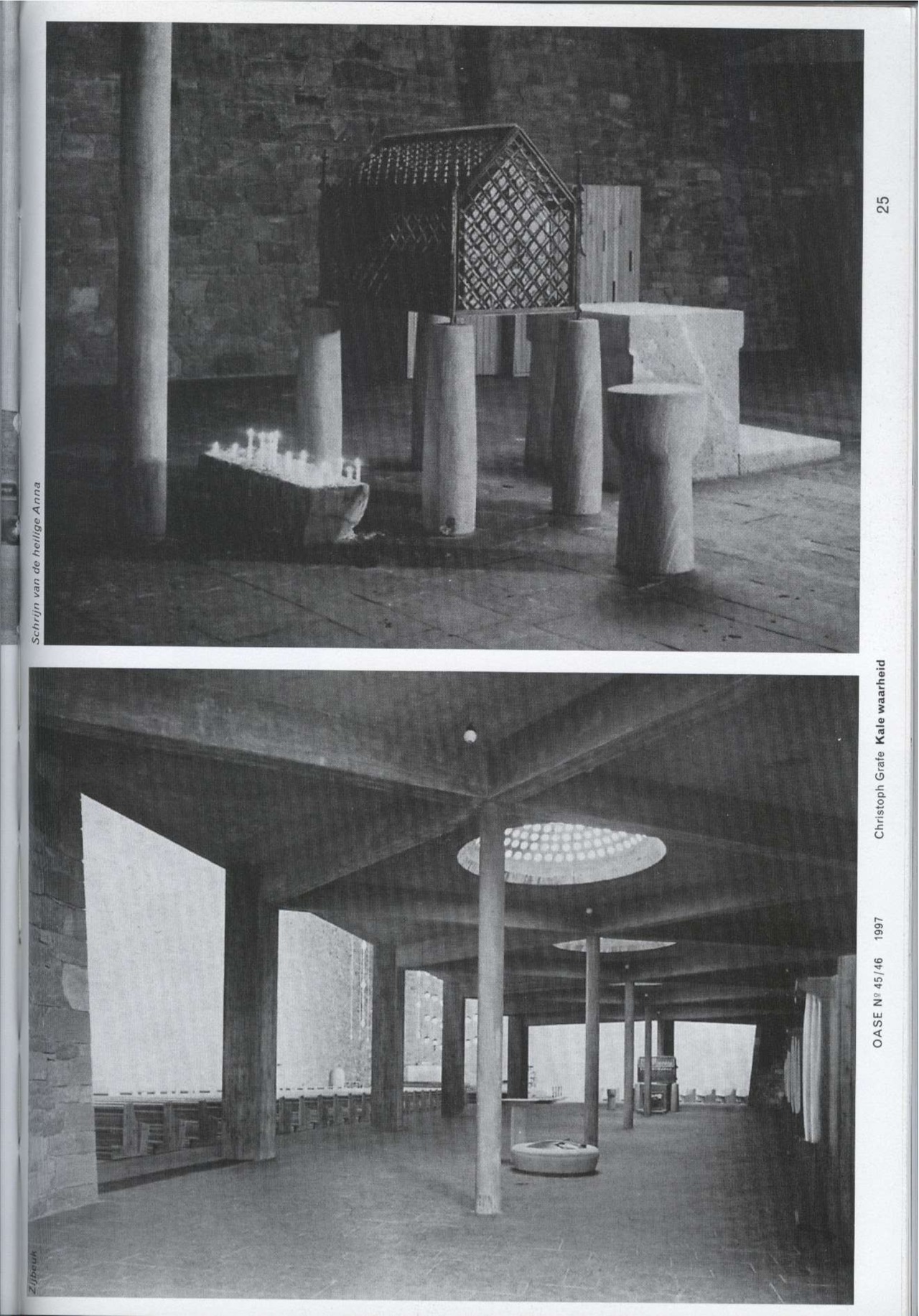

With the square windows set very close to the ceiling, light pours into the nave form everywhere. As a result, the nave is filled with an indefinable haze which makes one a little dizzy. Towards the altar the intensity of the light increases. Here the square windows form two vertical series meeting the horizontal band at the ceiling. The dark marble floor folds in a shallow flight of stairs across the whole width of the nave running towards the altar.(3) The marble block of the altar itself seems to grow from a geometrical landscape, providing a slight elevation towards the point of utmost intensity: the thirty-centimeter high crucifix standing on a humble wooden box at the centre of the altar. Otherwise the church is devoid of any images. Only the room itself and the surfaces surrounding it speak; the earthly, nearly black marble with its fine white pattern of veins which make lines like a landscape on a map; the smooth wall surfaces and the ceiling which, separated by a thin black line from the load-bearing walls, seems to float. The natural irregular pattern of the veins in the floor contrasts with the rigid pattern in which long columns of light fittings hang from the ceiling like a serial sculpture. This fundamental rule of treating the surfaces is only once deviated from. At the points where a constructive element is necessary to support the side wall of the nave, while the design does not tolerate any columns between the nave and the aisle, Schwarz finds pretext for an architectural detail of great beauty. A wall that can also be a column - and vice versa - and that distinguishes itself from the wall surface above by the black of its marble covering forms the backdrop for the cantilevered cubic pulpit.

Schwarz the theorist

In his book Vom Bau der Kirche from 1938, ten years after Wegweisung, Schwarz pursues the question of what this essence of architecture could be. In addition, the book is a sum of the experience of designing liturgical spaces, such as the Fronleichnamskirche and the chapel at Rothenfels.

Schwarz' argument is consistent with the argumentation he had set out in Wegweisung. If the form of a building is not given by tradition or a functional scheme, it is the architect's prime task to look for the significance of the building. To him the church is the architectural task in its ultimate essence. In a church the technique of construction meets a primal form of a human collective. In church construction the problems of architecture arise in their purest form. 'The art of building, as we meant it is not merely a walled shelter, but everything together: building and people, body and soul, the human beings and Christ, a whole spiritual universe - a universe, indeed which must ever be brought into

reality anew. We meant the primal deed of building, the process in which church becomes living form.'(7) Although Schwarz sees an inspiring translation of this fact in the medieval churches and cathedrals, he feels that the technical principles have now changed so much that there is no way back. The meaning of architectural concepts has shifted too much. 'For us the wall is no longer heavy masonry but rather a taut membrane, we know the great tensile strength of steel and with it we have conquered the vault. For us the building materials are something different from what they were to the old masters. We know their inner structure, the positions of their atoms, the course of their inner tensions. And we build in the knowledge of all this - it is irrevocable. The old, heavy forms would turn into theatrical trappings in our hands and the people would see that they were an empty wrapping.' (8)

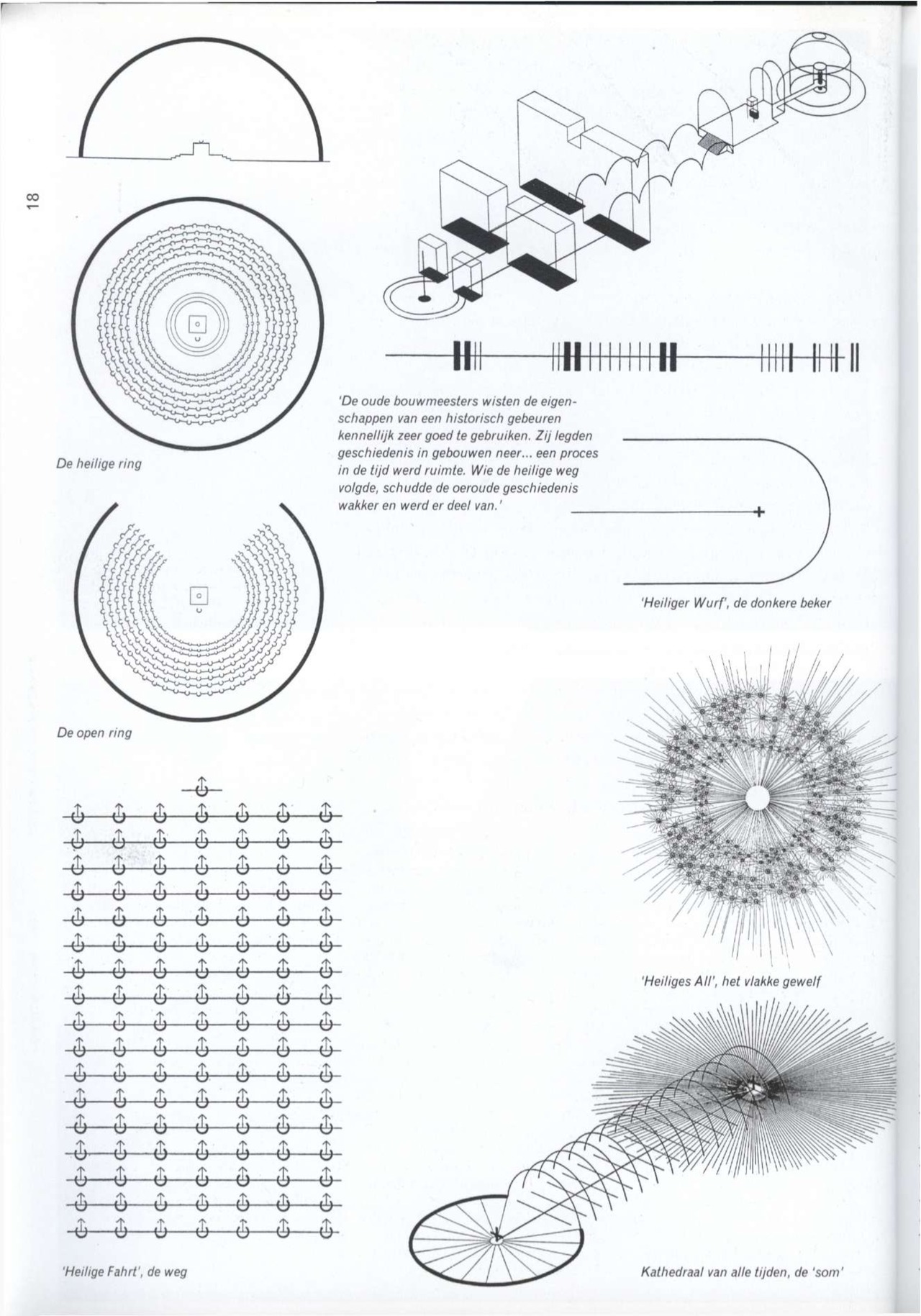

Against this background Schwarz formulates an archetypology of spatial forms. In part, these archetypes refer directly to the geometry of surfaces and bodies. Thus, the ring symbolises an introvert congregation sunk in prayer, while the open ring expresses a congregation ready to depart to a new future. Other archetypal forms are the way, the chalice of light, the 'dark' (infinite) hollow chalice, the dome of light (the universe) and the cathedral of all times which, in turn, expresses a divine entity. In Schwarz' work architectural forms are determined by geometrical rules. However, these rules are explicitly, not purely mathematically defined.(9) Geometric form is corrected by observation and perception of space. The visual and auditory perspectives and the physical perception of the qualities of material are put forward by Schwarz as factors that have to be considered in the actual spatial form. Gravitation and the dense mass forming the material are also factors in the perception and the process of realising a design.

A space is experienced through the whole body, the senses and the intellect. 'Indeed it is with the body that we experience building, with outstretched arms and the pacing feet, with the rowing glance and with the ear, and above else in breathing. Space is dancingly experienced.'(10) 'The farthest fingertip softly touches a thing, the gentlest power of communication flows out to it and slowly, softly it reveals itself.'(11)

The building is part of the same material world as the human body, it is a 'second' body. Originated through human movement, it is both solidified energy and a skin coming into contact with the 'dancing body'.

World War II and Post War Reconstruction

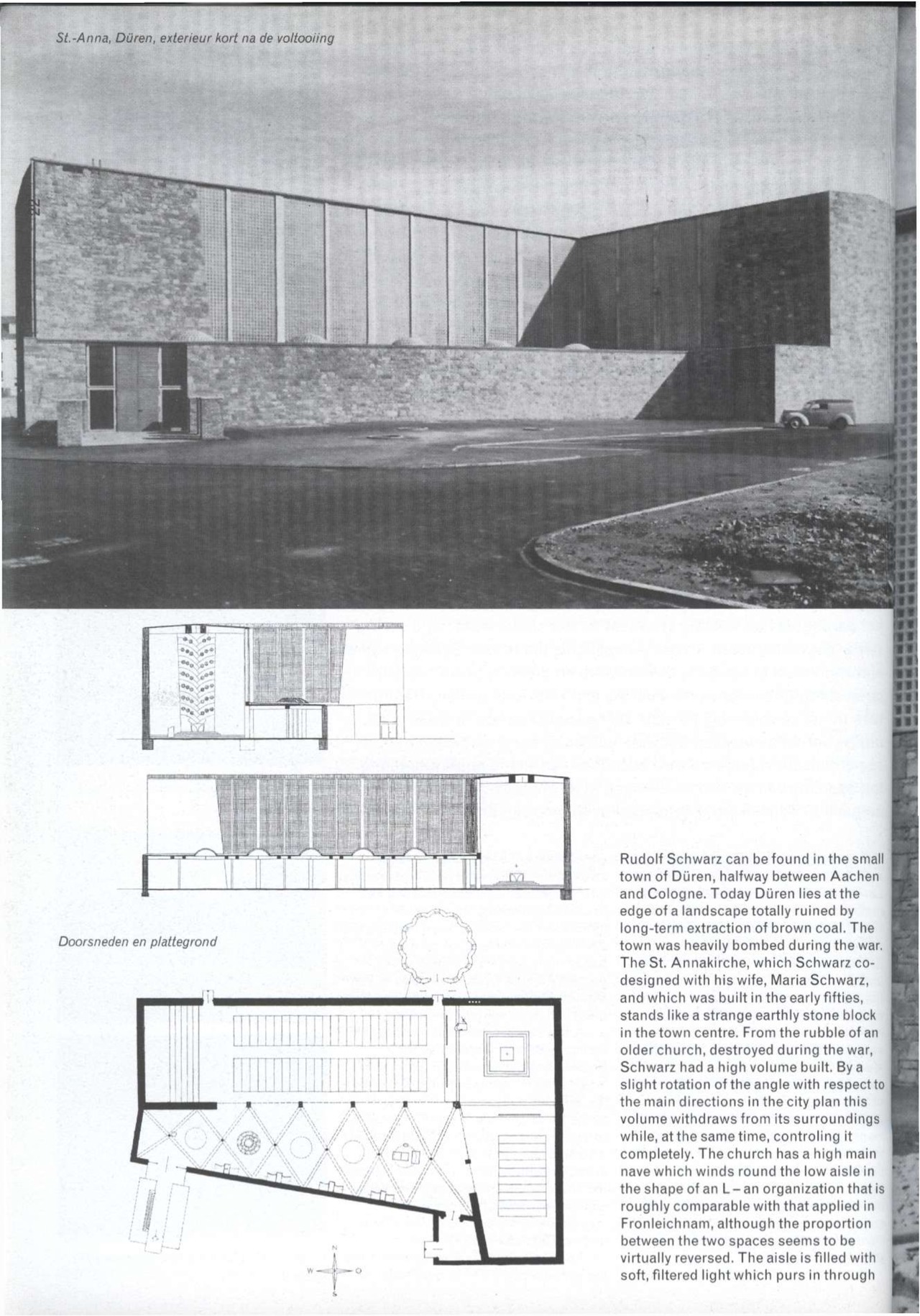

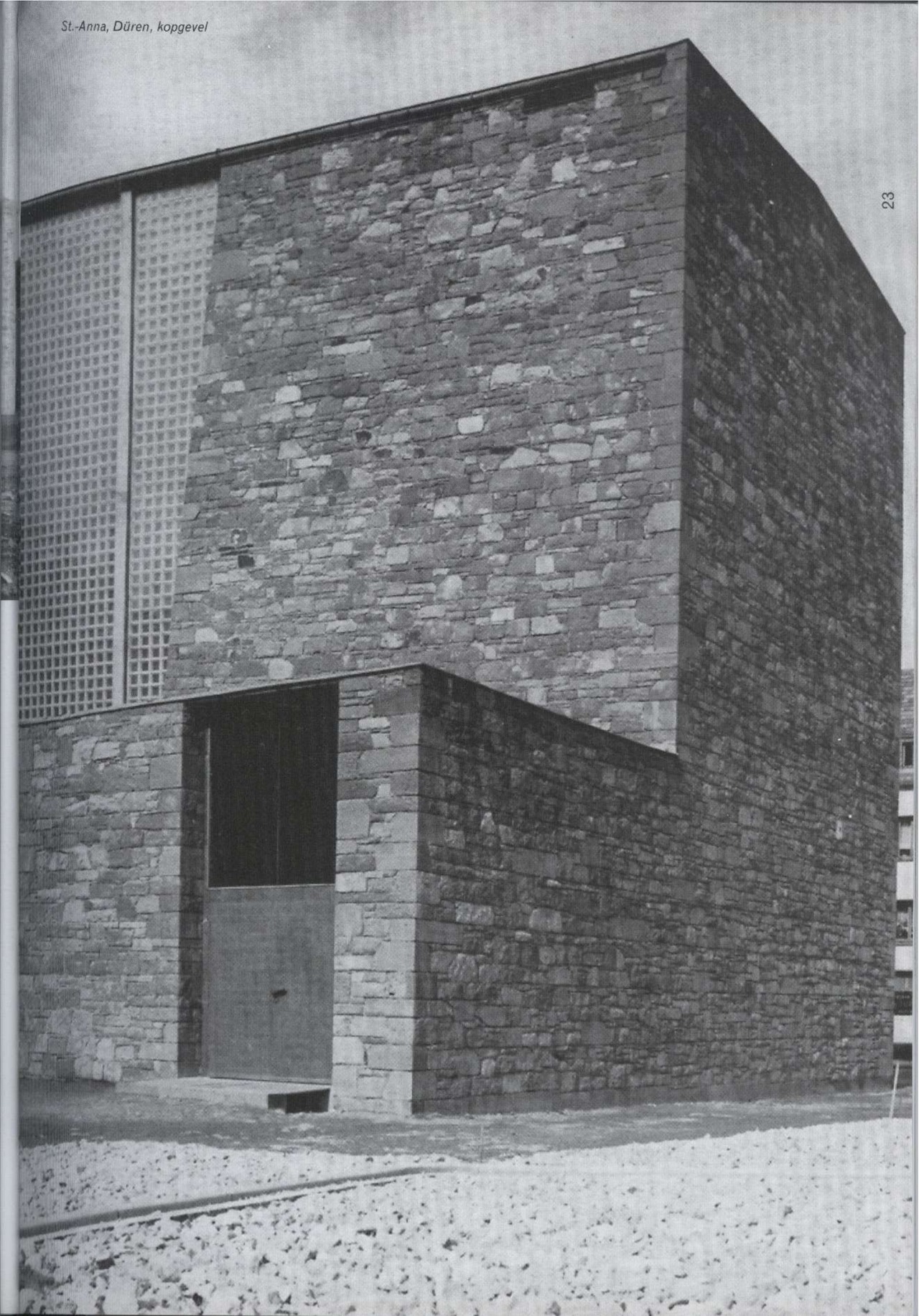

The rise of the National Socialists marked the start of a difficult period for Schwarz. Not only was the college at Aachen closed, the construction of churches too gradually ground to a halt. Schwarz is known to have said that he considered emigrating from Germany but was deterred from doing so by the idea of wandering through the world as a refugee. True enough, it is difficult to picture him as a exile in New York or California, like Mies or Mendelssohn. For some years he ran a small practice in Frankfurt. Then the new authorities put him in charge of the regional planning and Germanisation of occupied AlsaceLorraine. The arrival of the allies put a premature end to the whole plan and in 1945 Schwarz found himself in a US army camp. During his detention he was able to order his ideas on regional planning and, subsequently, to publish them under the title Von der Bebauung der Erde. The vision of society he sketches finds its translation in a hierarchic order of landscapes with central cities in which the identity of a landscape is being 'condensed'. This fitted in well with the Zeitgeist of the young West German republic, in which a corporatist-Catholic establishment, led by the Rhinelander Adenauer, had begun to restore an old order while the Cold War was at its height. Schwarz was not alone in his preoccupation with the identity of a geographical place, as can be seen from the records of the 1951 Darmstadter Gesprache in which he was asked to participate.

After the war Schwarz worked as Generalplaner supervising the reconstruction of Cologne, a heavily destroyed city. In addition to these activities he designed dozens of churches. The majority of the designs were realised and although the concepts of space are based on his prewar studies - and primarily on the types developed in Vom Bau der Kirche - their execution shows a great variety in material and idiom.

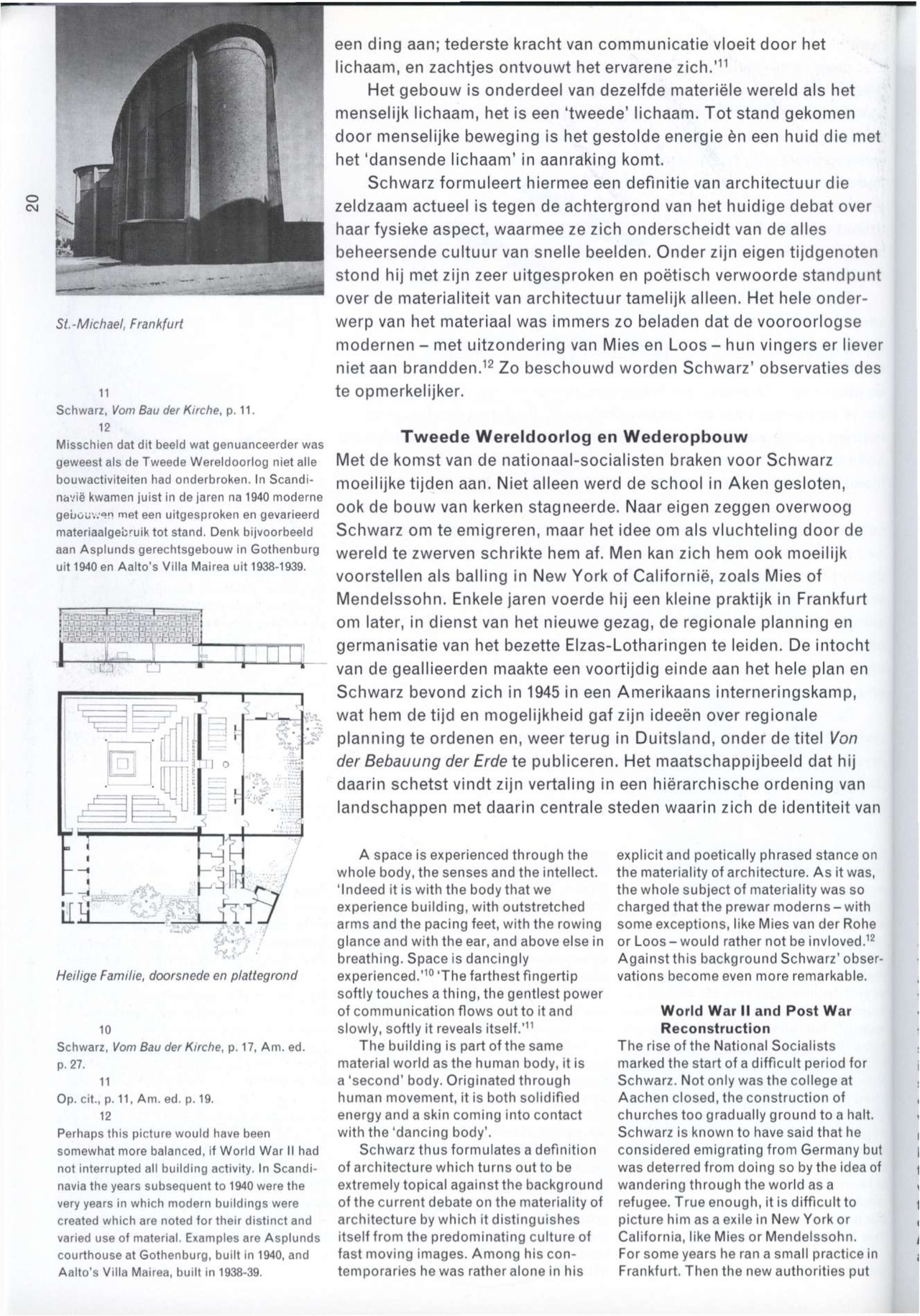

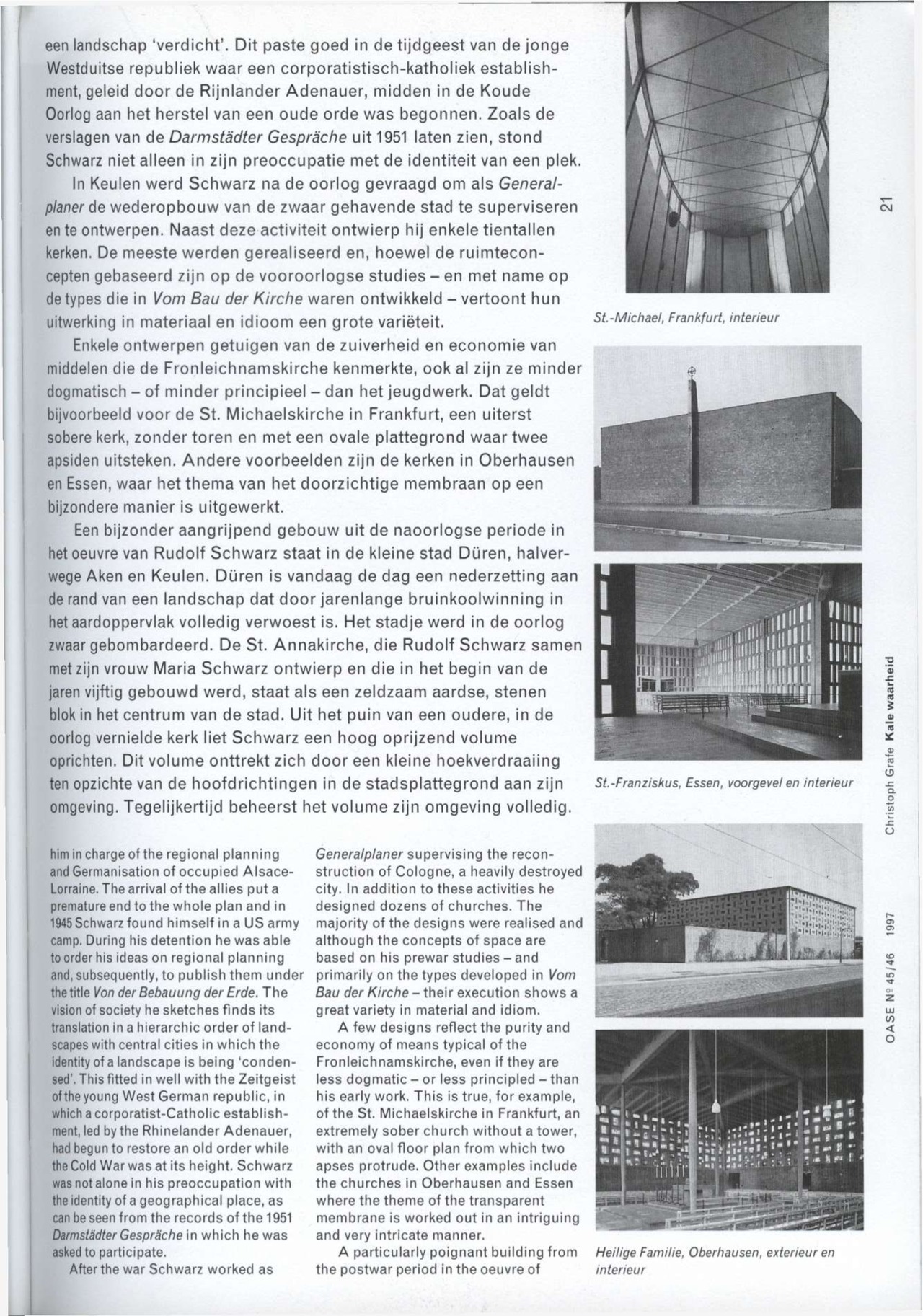

A few designs reflect the purity and economy of means typical of the Fronleichnamskirche, even if they are less dogmatic - or less principled - than his early work. This is true, for example, of the St. Michaelskirche in Frankfurt, an extremely sober church without a tower, with an oval floor plan from which two apses protrude. Other examples include the churches in Oberhausen and Essen where the theme of the transparent membrane is worked out in an intriguing and very intricate manner.

Perhaps Romano Guardini meant this when he wrote about the design of the church at Aachen: 'As far as the imagelessness of the sacral space is concerned: its emptiness is an image in itself. Rephrasing it without a paradox; formed in the right way, the emptiness of space and surface is not simply a negation of the pictorial character, but its opposite.'(14)

Translation: Sylvia Zaugg

notes

(1) Guardini was professor of Religionsphilosophie (philosophy of religion) and katholische Weltanschauung (Catholic ideology) in Berlin. Except on Schwarz, he also exerted a great influence on the thinking of Mies van der Rohe, who refers to Guardini in his personal testimonies. In 1939 Guardini was forced to leave the university. After the war he was involved in founding the Hochschule für Gestaltung at Ulm.

(2) Rudolf Schwarz, Kirchenbau, Heidelberg, 1960, p.9.

(3) When the church was adjusted to meet the requirements of the second Vatican Council, a second, centrally positioned altar was added, which slightly impairs the view of the original altar.

(4) Die Schildgenossen, 11th volume (1931), no. 17. As a matter of fact, Guardini is more critical of the exterior of the church which, according to him, lacks the intensity of the interior and which, by its white surface, presents itself both harshly and very vulnerably as it is difficult to maintain to its surroundings.

(5) Rudolf Schwarz, Wegweisung der Technik, 1929; reprint Braunschweig 1979. Mies van der Rohe called the text 'a breaking point in my development'. The relationship between Schwarz and Mies van der Rohe was one of mutual respect. Even after Mies' emigration to the United States the bond between the two architects remained intact. Mies wrote the preface to the American translation of Schwarz' book Vom Bau der Kirche (The Church Incarnate) and later, two years after Schwarz' death in 1961, he wrote an In Memoriam on the 'thinking architect'.

(6) Guardini's philosophy is expounded clearly and succinctly in the chapter on Mies van der Rohe in: Francesco Dal Co, Figures of architecture and thought. German architecture culture 1880-1920, New York 1990, pp. 262-286.

(12) Perhaps this picture would have been somewhat more balanced, if World War II had not interrupted all building activity. In Scandinavia the years subsequent to 1940 were the very years in which modern buildings were created which are noted for their distinct and varied use of material. Examples are Asplunds courthouse at Gothenburg, built in 1940, and Aalto's Villa Mairea, built in 1938-39.

Comments

Post a Comment